My 102-year-old cousin died last week. She was the sort of old person I aspire to be. At 97, she decided her walk-up apartment and cooking and cleaning for herself was getting to be a bit much, and moved herself into care, marbles intact.

I knew her quite well in her retirement, but I never met her family, who were well launched by the time I got to know her when I was a kid. One of them, I assume, wrote a nice obituary for her. Reading it made me think of times I spent talking to her, which was lovely. It also reminded me that I’ve been meaning to post about writing obituaries that will make you beloved by future family historians.

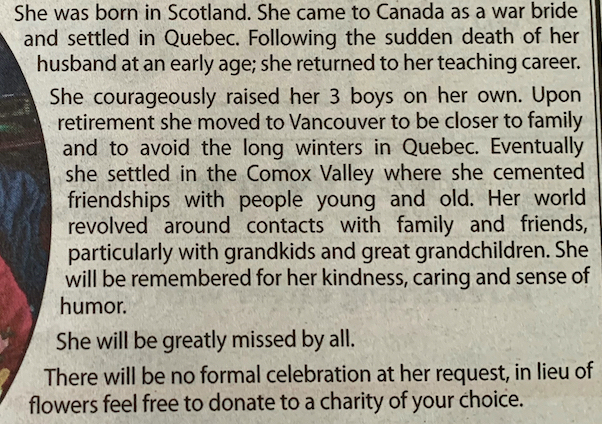

Let’s look at my cousin’s obituary as an example. This is the whole thing except her name and dates that were at the top:

From this obituary, I know lots of people cared about her. I like that there’s some hint of the sort of person she was and what people will miss about her. There’s some good general info about touch points in her life – born in Scotland, war bride to Quebec, retired to Vancouver, moved to Comox valley, had three boys. That’s all great. And there’s a photo of her. Bonus! All in all, a pretty decent obituary.

As a family historian, though, reading it was a rollercoaster: a long-ish obituary! A photo! HOORAY! This is the kind of thing we live for, finding details about someone that give us some insight into the person and confirm what we think we know…But… wait. It doesn’t have any specific details. SADNESS! So many tantalizing hints, but almost nothing to go on for genealogical research purposes.

I love obituaries that give more than just names and dates, that give a sense of who someone really was, whom and what they loved and what sort of personality they had. I’m all for that. But if you want to write an obituary that will be genealogy gold to future family historians (and, for that matter, to people reading it at the time who might not otherwise recognize the connection they have to someone who’s died), that’s only half the equation. The other half is specifics: who, when, and where in particular, in as much detail as you know.

What would that look like? Let’s say my cousin was Mary Smith (all details made up):

Mary née Smith was born in Glasgow, Scotland on June 1, 1919. She came to Canada as a war bride in 1945, settling in Montreal, Quebec. Following the sudden death of her husband John Doe in 1960, she returned to her teaching career until her retirement, helping a generation of Francophone students learn English.

She courageously raised her three boys Tom (Jane), Dick (Joan), and Harry on her own. Upon retirement, she moved to Vancouver to be closer to family and to avoid the long winters in Quebec. Eventually she settled in the Comox Valley where she cemented friendships with people young and old. Her world revolved around contacts with family and friends, particularly with grandkids Martha (Jenny Black) and John (Barbara) and great grandchildren Katie and Misty Doe and Ethan Black. She will be remembered for her kindness, caring, and sense of humour by all who knew her.

Same obituary as it was originally, but with more specific detail added for which future descendants longing to know the people who came before them will thank you.

Writing an obituary is one of so many tasks that have to be done while people are grieving and often don’t have the bandwidth to dig up more details than they know off the top of their heads. They just need to get it done. If you have an “info for my executor” file of some sort – and you should – one that says where the will is kept, what bank accounts you have at which banks, where you keep the key if you have safety deposit box, who needs to be told of your death (with contact info for friends, colleagues, online and in-person groups you belong to, etc.), your funeral and burial preferences, and any other helpful stuff that ensures the people who’ll have to deal with it have all the information they need when you’re not around to ask – you might consider adding a sheet of details for use in your obituary. Dates, names, and places that have been important to you are a good start, even if they seem obvious to you (like your children’s and grandchildren’s and their partners’ names correctly spelled) and will make things easier for whoever has to write about you after you’re gone. Or go ahead and write a draft if you’re feeling creative. Even if they don’t use it, they’ll hear your voice when they find it, and that’s a gift in itself.